Particulate flow modeling

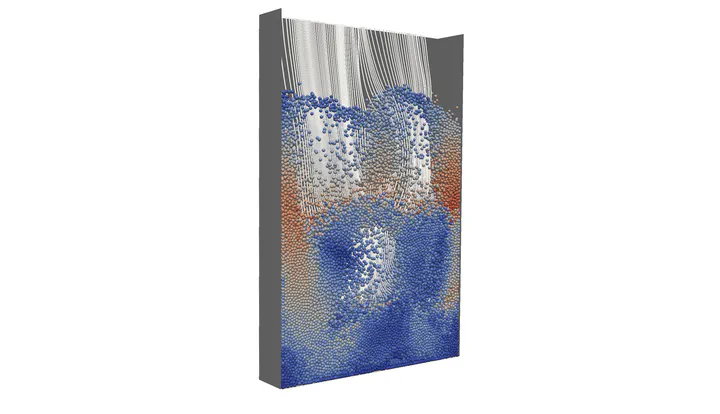

Fluidized bed with transparent front. Particles are colored according to their velocity, gas stream lines are shown in white.

Fluidized bed with transparent front. Particles are colored according to their velocity, gas stream lines are shown in white.Granular materials are composed of discrete macroscopic particles with diameters ranging from micrometers (e.g., fine powders, dust) to several centimeters (e.g., rocks in riverbeds, ore grains in steelmaking plants). Computational particle simulations have become essential tools for understanding and predicting the complex, emergent behavior displayed by such systems over a range of regimes including dense, pseudo-steady (e.g., moving beds) and dilute, dynamic (e.g., fluidized beds) flows.

The scientific interest in granular materials stems from their inherently multiscale nature. A long sequence of short-term interactions (involving the exchange of mass, momentum and energy) of many small particles with each other and with the surrounding fluid phase gives rise to macroscopic bulk flow properties. Bridging this spatio-temporal multiscale problem is a challenging, active area for fundamental research.

From an application-oriented perspective, granular materials are ubiquitous in various industrial processes (e.g., agriculture, mining, pharmaceuticals, and steelmaking), yet their plant-level behavior remains poorly understood. Inefficiencies or unexpected events can lead to costly production losses. Particle simulations provide a means to better understand and optimize existing or develop novel processes. Especially for energy-intense industry branches such as steelmaking, reliable computer models will play a crucial role to drive innovation in the course of decarbonization.

Among a variety of available modeling approaches for particulate flows, my research mainly involves Euler-Lagrange methods such as CFD-DEM simulations. The fluid dynamics is governed by the Navier-Stokes equations, particles interact via simplified contact forces, and appropriate interphase coupling terms account for the interaction between particles and fluid. The computational representation of discrete particles allows for a detailed description of, e.g., different modes of heat transfer and heterogeneous chemical reactions. However, large numerical costs limit the scope of this kind of method to seconds or minutes of real process time, which is far below relevant time scales. My research focuses on the combination of such detailed, physics-based models with different data-driven approaches to accelerate simulations of large-scale, long-term flows towards real-time capability and beyond.

References for getting started on the topic of particulate flow modeling: